Teaching Git: towards an advanced Git course

By Florencia D'Andrea in Reproducibility Git

December 15, 2022

What Git commands should be included in an “intermediate” or “advanced” Git course? Is there any logical order to teach Git commands that can facilitate the student’s learning? How many commands and/or topics you should teach before introducing git cherry-pick?.

Can the order we teach the Git commands affect how easy is to learn them?

What do you think? I started thinking about this from my experience teaching and re-designing a Git course. As I will mention later, it could imply more effort on the instructor’s side to introduce git stash than git reset at the end of a class. Is there any king of dependency among commands?

Proposing dependencies between the themes/commands to be taught could be useful for:

-

Organize and/or design Git classes at different levels.

-

Help to have a pre-selection of material and activities to cover potential gaps in learning, even if they are not a class topic.

This could also be useful considering that many students’ questions about Git emerge in courses not focused on Git, but which involve intensive use of this tool. For example, students could experience Git issues during capstone projects or project-based courses.

- It can encourage discussion and exchange with other instructors, improving the material for subsequent offerings of these courses.

Before start thinking about this, let’s start by exploring what is covered in advanced Git courses.

What commands are covered in intermediate/advanced Git courses?

I explored some courses offered online to see if there is some kind of pattern in the commands considered intermediate/advanced.

-

LinkedIn - Git intermediate techniques - Rebase, cherry-picking, staging, branch management techniques.

-

Atlassian - Advanced Git tutorials - Merging vs. Rebasing, Resetting, Checking Out, and Reverting, Advanced Git Log, Git Hooks, Refs and the Reflog,

git prune, Git subtree, Git LFS,git gc, Git LFS, Git Bash,git cherry-picking, Git submodules among other topics. -

Toptal - The advanced Git Guide -

git rebase,git squash,git bisect,git stash,git reset, andgit revert. -

Udemy - Git: Advanced commands -

git commit --amend,git reflog,git rebase,git config --global alias,git fetch --prune,git reset [both soft and hard resets],git clean,git revert,git cherry-pick,git stash,git tag, Squash and Merge, Rebase. -

GitKraken - tutorials

- Git Intermediate -

git merge,git stash, Git hooks,git squash, pull requests,git rebase,git cherry-pick - Git Advanced - Solving merge conflicts, Git LFS, Git submodules.

- Git Intermediate -

Even if there are some repeated commands among these courses (git rebase, git squash and git cherry-pick seem some of them) there are other interesting inclusions. Is teaching solving merge conflicts an advanced use of Git? Or it is introduced at the same time than when we are teaching pull requests?

Even if thinking on this was useful, to continue thinking in the order of potential commands to teach we have to consider what we want to teach first:

Is teaching Git equal to teaching Git commands?

This question is clearly answered in chapter 5 of Teaching Tech Together (Wilson (2019)):

“Your goal when teaching novices should therefore be to help them construct a mental model so that they have somewhere to put facts. For example, Software Carpentry’s lesson on the Unix shell introduces fifteen commands in three hours. That’s one command every twelve minutes, which seems glacially slow until you realize that the lesson’s real purpose isn’t to teach those fifteen commands: it’s to teach paths, history, tab completion, wildcards, pipes, command-line arguments, and redirection.” -Wilson (2019)

Dealing with abstraction is probably one of the major challenges of teaching sciences. One strategy that can help educators to explain highly abstract topics is to work with representations or mental models, organized in a narrative.

Mental model: A simplified representation of the key elements and relationships of some problem domain that is good enough to support problem-solving. -Wilson (2019)

Being able to become a skilled Git user implies operating with abstraction. In my experience, teaching only with live coding could be not enough. There should be some extra effort in order to support the creation of a mental model for the students.

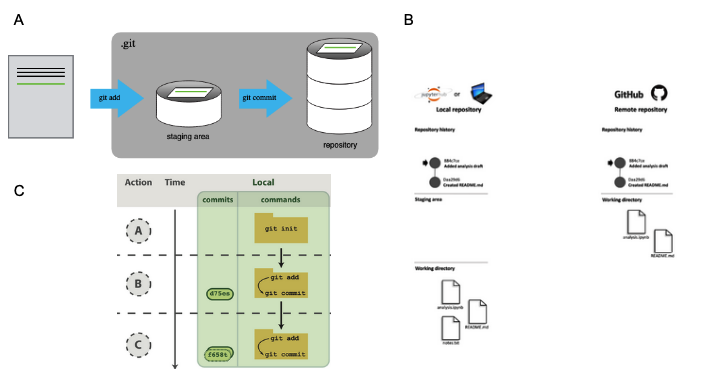

In Git context creating a representation often implies not only defining the relationships (in many cases represented by the Git commands) but not describing some compartments where the commands operate. It is common to find explanations in initial Git courses about what the staging area is, for example, to can understand basic commands such as git add and git commit.

From now on, I will talk about commands and compartments as two different elements of my representations.

A representation to catch them all?

Not only there it could be more than one mental model needed to explain Git to a class, if not that the each representation have different grades of complexity.

There are many representation on how to teach Git, and there should be carefully selected in relation to our learning objectives to avoid confusing the students.

Oversimplifying, I can think in at least two: one to teach the Git basic workflow, that can have different grades of complexity and a second one, more advanced, to teach branching.

I will supply an example that can fit my classes:

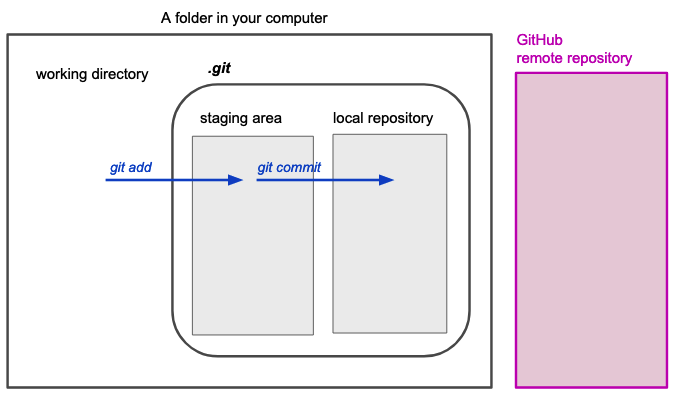

Initial mental model: Step 1

compartments: Working directory, staging area and local repository

commands:

git addgit statusgit commitgit log

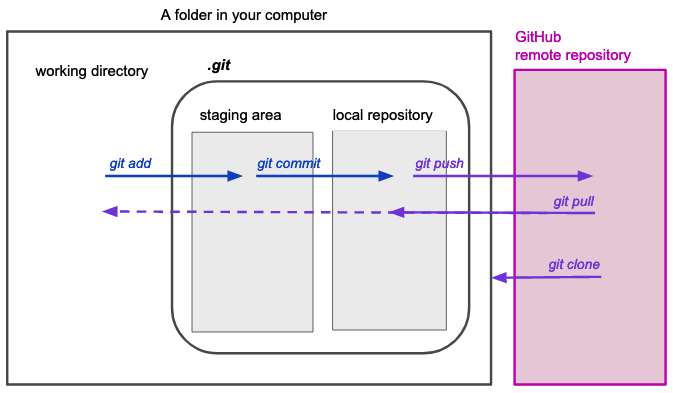

Initial mental model: Step 2

new compartment: remote repository

commands:

5. git clone

6 and 7. git push and git pull

Why?

-

The working directory and the repository itself and how all these compartments are linked deserves some explanation.

-

I am considering

git logandgit statuspart of this first basics commands as they are keys to depict what is going on in both areas and help us to depict the model.

Special case:

git pullThe commandgit pulldeserves a spetial section as to fully understand it mix betweengit mergeandgit fetch

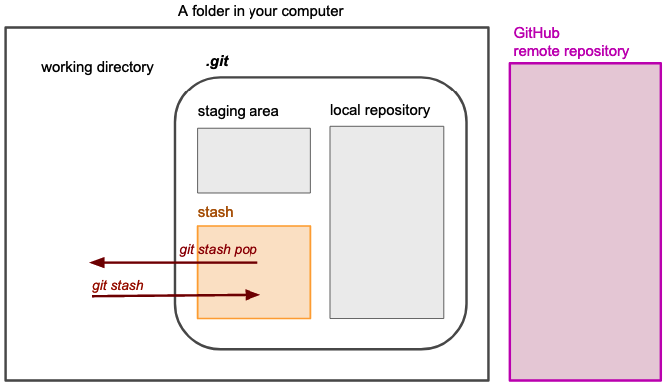

Initial mental model: Step 3

new compartment: Stashing area

command:

10. git stash

The example of a more advanced command for out first mental model would be git stash. This was one of the commands that appear listed as advanced in some of the courses I mentioned before.

Why?

- Even if we are still working with the same areas or compartments, understanding how it works implies adding a new area to the mental model the students have built so far. This means that not only the student should understand what the commands does if not how this new area interacts with the rest of the compartments and that is located inside the

.gitfolder.

AS I mentioned at the beginning of this blog-post, it could imply more effort on the instructor’s side to introduce git stash than git reset at the end of a class, exactly for this same reason: it is needed more explanation to understand this command better, it is needed to understand how to

Tell me the Git mental model of your student, and I will tell you what command to teach…

Now, imagine that you are designing a class when you teach the commands 1-10. Now, you decide that you want to include the commands git reset --hard and git reset --soft. Where in this sequence would you teach them?

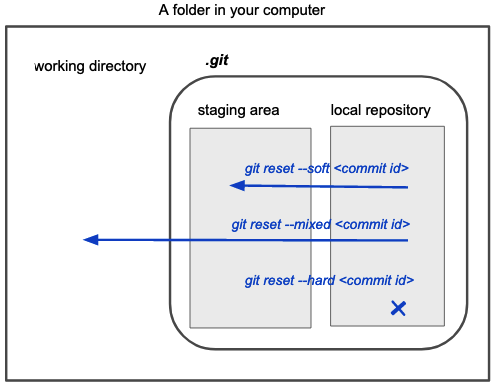

git resetis a command that deletes the project history. In a difference matter to other commands, the flag--hardand--softare pointing where the information should move.git reset --hardwill simply delete the history of the project, butgit reset --softwill dissolve the commit and sent the information contained inside it to the staging area.

Why?

The students doesn’t need more than the compartments taught in the initial mental model: step 1 to learn this commands. So, if the learning objectives allow us, these commands could be teach after the basic workflow without much explanation, as it not really needed to introduce the remote repository to understand what these Git commands do.

This being said, with git reset --hard and git reset --soft we are considering for the first time that flags can alter significantly the action of a command. For students that are learning coding at the same time, this could deserve an extra explanation about how flags work.

Second mental model: Branch-related commands

In my opinion the hardest part to work with Git is the complexity and amount of Git commands and abstract representations needed to fully understand it. Branching, for example, introduce concepts that are completely different than the representation we have been working on and deserves a special explanation. That is why, considering pull request or git merge “intermediate” or advanced git commands seems an interesting idea.

Not only instructors have to consciously define the mental model that we want to build with the students on advance, if not that each mental model can have different stages or advanced representations, and necessary more than one mental model should be introduced to cover an advanced course.

I have created a special project called “Teaching Git” that will cover how this must evolve.

Some final ideas:

-

Educators should define in advance one (or more) Git representations they are expecting the students to manage at the end of a course. For example, there could be one mental model for teaching the basic Git workflow and then move to another one to teach branching.

-

If an educator should add more material to a lecture, it is riskier to incorporate commands or concepts that are not covered by the mental model that is expected for this course or course section. There should be a considerable amount of exercises or explanations assigned to help the student to move to a new stage of the representation. If there is not enough time or material available for it, it is better to not add commands or exercises that can be solved applying the same representation. For example, adding the command

git restoreto the initial mental model should not be particularly challenging, as there are not new compartments to teach. -

The mental models evolve from beginners to advanced users, and can have “intermediate stages”. Also, there could be completely different mental models interleaved in a full Git course. If the educators are conscious about the representations they are helping to build, they create / select activities that allow the students to transition to new stages of the same mental model or to a different model.

Towards and advanced Git course

This blog post was born as a side-product of my project “Git Instructor Kit”. My goal is to support instructors that want to improve pedagogically at the time of teaching Git and also help to build/compile a full set of exercise and activities that could help instructors to create these Git courses.

Akwonledge

I would like to thank the CONICET researcher Juliana Benitez for her comments about this blogpost.

References

Blischak, John D, Emily R Davenport, and Greg Wilson. 2016. “A Quick Introduction to Version Control with Git and GitHub.” PLoS Computational Biology 12 (1): e1004668.

Munk, Madicken, Katherine Koziar, Katrin Leinweber, Raniere Silva, François Michonneau, Rich McCue, Nima Hejazi, et al. 2019. “swcarpentry/git-novice: Software Carpentry: Version Control with Git, June 2019.” Zenodo. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3264950.

Timbers, Tiffany, Trevor Campbell, and Melissa Lee. 2022. Data Science: A First Introduction. CRC Press.

Wilson, Greg. 2019. “Mental Models and Formative Assessment.” In Teaching Tech Together, 7–16. Chapman; Hall/CRC.